More Steps Ahead

So we learn more to leave more. Increased knowledge of self is meant to lead to increased surrender to God.

But how exactly? And then what?

First, there is no surrendering but by prayer.

Tell Him

In 1 Peter 1:5, when Peter commands us to “humble ourselves … [by] casting all our anxieties on [God],” he means for us to pray.

How else would that work? I understand him to mean that we cast our anxieties on God by saying, at least, “Here, Father, take this anxiety.”

We just tell him.

That doesn’t mean we merely think it on the go, as if we’re only checking a mental box while we multitask. Now sometimes when we’re moving throughout the day, all we’ve got are the “arrow prayers” we shoot up: “God, help!” and “I need you!” and “Lead me!” This is good. It’s something we might call breathe-praying — every moment is coram Deo, before the face of God! We want to keep in step with the Spirit (Galatians 5:25)! We want to live in the light of God’s nearness! (Psalm 139:7–10)! We never want him too distant in our thoughts.

But it’s also important that we set aside moments for “real prayer.” (And look, I don’t especially like saying it that way, but I don’t know what else to call it.)

By “real prayer,” though, I mean a moment when you determine to pray, and you stop doing anything else. Your mind and body are synced up, maybe by your bowed head and closed eyes, or maybe by your folded hands, maybe it’s your head in your hands, maybe on your knees, maybe prostrate on the floor with hands stretched palms-up. Whatever you mean to do, you do that, and then you say, “Here, Father, take this anxiety.” And you name it as best you can. You name the fears. “Take it, the […]” “Help me with […]” And maybe you say it aloud, just so you hear yourself saying it to God. And maybe then you weep, or maybe you laugh — I don’t know. But you’re surrendering. You resign: I am not. I cannot. I will not.

And then what?

You take the next step. God, you are. God, you can. God, you will.

Moving On

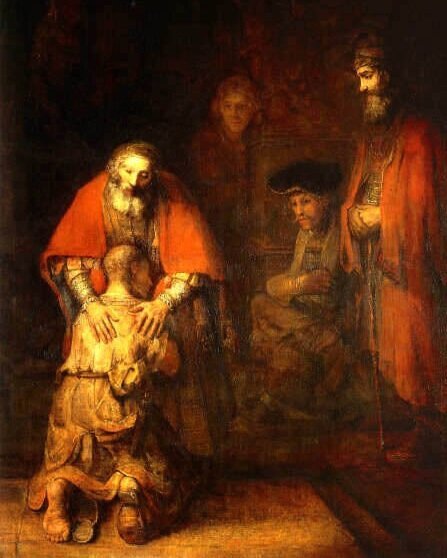

Rembrandt helps us here. In his famous painting of the prodigal son returning to his father, it’s been noted that the father’s two hands look differently. The son is knelt before the father who stands, and the father’s left and right hands are enveloping the son in a kind of hug. The father’s right hand is smooth and tenderly placed on the center of the son’s back while the left hand is veiny and embraces the son’s shoulder. The difference is subtle, but it’s there. The one hand is motherly and compassionate, the other is fatherly and firm. But that’s not all. The father’s two hands correlate to the son’s feet, one which is bare and wounded, the other which is covered and worn.

From our perspective, as we look at the painting, the tender hand is on the side of the wounded foot. The firm hand is on the side of the shoe. The experts are eager to point out the genius of Rembrandt here, explaining that he intends to show us the heart of God, compassionate and firm. Responsive and purposeful.

The tender hand shows us that God receives us as we are, in all our brokenness, with all our hurts, all our past mistakes, with the scars of sin done by us and to us. God “heals the brokenhearted and binds up their wounds” (Psalm 147:3). That is what the barefoot needs.

The firm hand, however, shows us that God intends to lead us from here. He doesn’t mean for us to lay in the sickbed forever, barefoot, wounds undressed and louder than anything else. “Put your shoes on, child” is what the embracing hand seems to say. “Because you’re not finished here. I’m not through with you.”

That is a message we must hear from our father. That is mercy in full.

We learn more to leave more, and then we must go to work. Or take the kids to school. Or answer those emails. Or rake the snow off the roof. And follow Jesus. And love people. And give generously. And spread encouragement. And sit with friends. And intercede for others. We move on.

We don’t “move on” as in forgetting the past, or pretending the wounds weren’t real. This is not about “getting over it.” That’s not what the firm hand means.

We move on, with the sound of the party still ringing in our ears, the fatherly embrace still imprinted in our memory. The scars are still there, but the father’s best robe is wrapped over our shoulders, his ring is on our hand, and he’s put shoes on our feet. Is that firm hand the hand of a cobbler? Perhaps. God is compassionate and commissioning. He has more steps ahead for his children. For you, brother and sister. He’s not through with you.