The Pursuit of Manhood

Cities Church Men’s Breakfast | June 8, 2024

Introduction

Disclaimer:

This is not a sermon, and

my audience is not mixed — it’s only men.

This means that I will speak differently than how you’re used to hearing me. I’m not doing biblical exegesis (which is where I’m most comfortable), but, instead, I’m going to try to speak as plainly as I can about reality, leaning on Scripture and natural theology (which includes insights from anthropology and developmental psychology). I’m not going to nuance and qualify everything as I might for a mixed audience. There is a whole lot more that could be said about everything I say — I’m only saying some of it today.

Let’s pray:

Father in heaven, in Christ, you indeed are our Father and we are your sons. You are the God of armies and we are your soldiers. By your Spirit and his power, guide us today as we look at this important topic. In Jesus’s name, amen.

The goal of this message is to convince you that being a Christian is the fulfillment of your manhood, and in no way contradicts it. That’s the thesis. It’s going to take some time to get there, and I want to start by telling you why you should be interested in this topic.

Why This Matters

There’s several reasons I could give you, but the top three reasons you should care about the topic of manhood is …

1) You are a man.

How do I know that I’m a man? This is a key question. [If you’re a man, raise your hand.] How do you know this? There are three inputs — the biological, societal, and psychological.[1]

First, I know I’m a man because I have a penis and my nipples don’t work. This is biology. It’s God-given. I’m XY, and I have the anatomy that proves it.

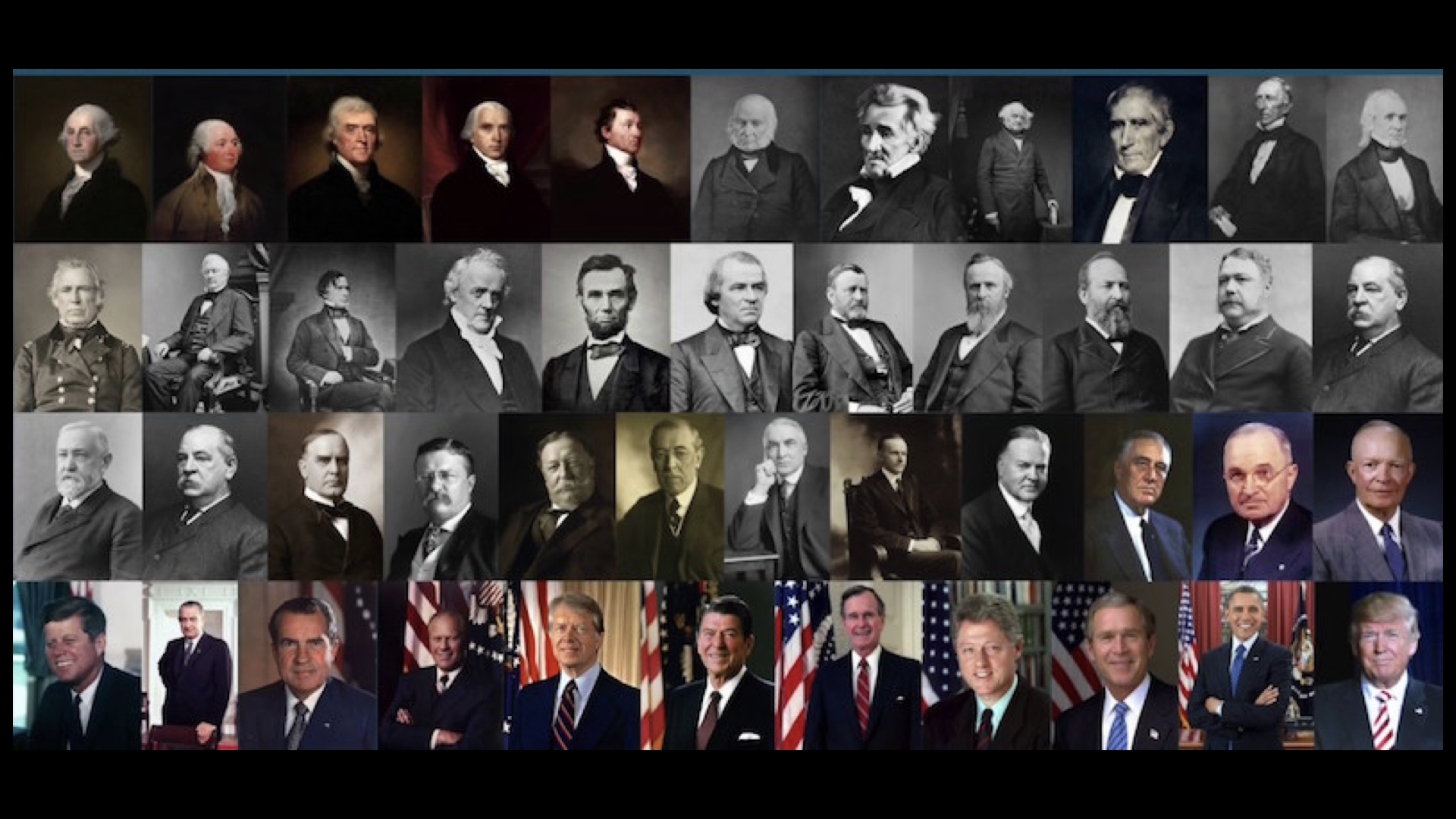

Secondly, I know I’m a man because my society recognizes me as a man by my behavior. I adhere to masculine markers, such as that I dress like a man in accordance to our cultural expectations (which, by the way, men’s dress in the Western world has changed very little for hundreds of years — pants, a button-up shirt, a jacket, and some kind of ascot. George Washington and Joe Biden, and every president in-between, have this in common. It’s the Western man’s go-to, and it’s constancy is remarkable). I also act like a man in accordance with my community’s social standards and expectations, which includes my church’s.

Thirdly, I know I’m a man because I feel like a man — my psychological identity is masculine. I feel like a man and I want to be a man.

This third input was not even recognized in previous generations. It’s only started to register for people because of how our society has responded to gender dysphoria (that’s basically when someone is a man in terms of biology and society but they don’t feel like a man on the inside). In previous generations, and in the remaining sane cultures of the world, you’d respond to that situation like this: Well you have male parts and we recognize you as a man, so you need to work on your feelings.

But today, in America, we instead say: Oh, you don’t feel like a man? That means we better cut off your penis and have you start dressing like a woman. It’s Satanic. It makes our psychology the normative perspective on the human experience. Everything is based upon what you think and feel — so absolute truth is denied; everything is relative; you become your own god. It’s a destructive ideology.

I wrote about this ten years ago in the book Designed for Joy. It was a team-book on sexuality and I wrote the first chapter on manhood. And I still believe what I wrote there. I’d only double-down and add to it.

So, I care about this topic because I’m a man. You should too.

You should care about this topic because …

2) It’s hard to be a man.

The pressure and weight of being a man is overwhelming at times, and we’re not supposed to talk about it publicly in mixed groups. There’s some social shame waiting for us if we do. It’s been shoved down our throats that being a man is strictly a privilege — so we can’t say it’s hard.

But objectively, it is hard. The facts are undeniable that in every critical statistic in the area of longevity — disease, suicide, crime, accidents, childhood emotional disorders, alcoholism, and drug addiction — men are negatively affected at a disproportionately higher rate. Throughout history, in every culture, men die younger than women.

Now at one level, it’s always been hard to be man (it comes with the calling — we’ll get there), but at another level, the existentially, I think it’s never been harder to be a man than right now.

Here’s why: men have always been the most dispensable sex of the human species. That’s one reason historically it’s been men who fight our wars and run into burning buildings and patrol our streets. It’s women and children in the lifeboats first — the men are expected, naturally, to sacrifice their lives. Because — from a biological perspective men are not as essential as women to the reproduction of humanity. Men are vital to the leadership, provision, and protection of humanity, but not as vital to its reproduction. Think about this …

Question: How long is a man’s part in procreation?

Answer: Not very long — especially compared to a woman’s, which is at least nine months, not to mention breastfeeding, which often continues for the child’s first year. Podles writes, “The male can die and the species still reproduce. But if the mother dies before the child is capable of taking care of itself, the child will die and with it the hope for the propagation of the species” (The Church Impotent, 38).

Men have always had less a part to play in reproduction of humanity, but they’ve made up for it in the sustenance of humanity. So, the man plays his short part in procreation, but he then goes out to protect and provide for woman and child. That’s always been the case.

But today, it’s not just that men still play a smaller part in reproduction, but there are storage freezers everywhere across the world that are hosting the man’s part in vials. If every man on this earth were suddenly wiped out, we’d be surprised how much reproduction could go on without us.

And as far as the man’s part to sustain humanity, to defend it, feminism came along in the 20th century and said that a woman can do everything a man can do. So now you’ve got women soldiers and women firemen and women sheriffs, and now add to this the rise of technology and A.I. — technological advancements and trans-humanism is one-hundred percent more a threat to men than women.

Men, know that society cannot work without you — but there’s something dark in our society that wants you to think it can. And the result is that men are lost.

You may not feel this acutely right now, but in general, our world has devalued men, and it has created a psychological crisis for men, even Christian men. Maybe especially Christian men … It’s hard to be a Christian man. And a lot of you know this.

If you shrug that off right now, and you think it’s not a thing, it’s probably going to knock you flat on your back one day. I’m not even 40 yet, and I’ve seen more men than I can count on my hands ruin their lives … and you know what happens when a man ruins his life? He always takes down more people than himself — sometimes we’re talking generations. And men ruin their lives, and make ruin, because they get lost. I don’t want to get lost. I don’t want you to get lost. This is bigger than life and death for me. We should care about this.

You should care about this topic because …

3) We need future men.

They’re called boys. I have four boys who I love with every fiber of my being and God has called me to show them what it means to be man.

So this is something I started working on deliberately in 2018 when I defined five character traits I wanted my sons to develop. I wrote them out and defined them, printed a small poster and taped it up in their room (there’ve been a few iterations of it, and currently it’s a framed version that comes with a legendary tale of their distant (fictional) ancestor, Methuselah Parnell, a pirate who became a Christian.) We made hats with an acronym on it — each letter stands for a trait. We talk about these traits all the time and pray about them. They’re about manhood.

And most recently, my oldest son turned 13, and we marked it as the start of a five-year initiation into manhood, which means my own manhood is at a more crucial place than ever before. [2] As a father, as your children grow, everything becomes a teaching moment. There is an unrelenting pressure to be an example of a man for my sons, and to be the standard of a man that my daughters will marry. That’s true for every father. You should care about the topic of manhood.

* * *

We’ll get there in two points:

I. The Meaning of Manhood

Now I said earlier that “we are men,” but I need to explain more about this. What I said could have been an overstatement, and the reason why is because maleness and manhood are not the same. Manhood is the result of an equation: Maleness + masculinity = manhood.[3]

Maleness is God-given (it’s sexuality, biological). Masculinity is natural in that it extends from God-given maleness, but it is culturally informed. What is considered masculine in one culture is not universally applied to all cultures — now, to clarify, that there is such a thing as masculine is universal, but there the particularities can be different. Similar, yes, but not identical.

We see this in Paul, in 1 Corinthians 11:14. Paul says that it is a disgrace for men to have long hair. According to Greco-Roman culture it was not masculine to have long hair like a woman. That is particular, but what is shared across all cultures is that there is a masculine way for men to wear their hair, or, we could say more generally: there’s a masculine way to do appearance. That’s behind what Paul is saying. He’s making two universal statements here[4]:

it is not right for men to act or present like women; and

society influences the norms of masculine and feminine expression.

Masculinity is real. Every culture has an ideology of masculinity. That’s a phrase that comes from David Gilmore.[5] Gilmore is a social scientist who has written a lot on masculinity, and his big work is Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity. Basically, he does vast research in several different cultures — Micronesia, Melanesia, equatorial Africa, aboriginal South America, South and East Asia, Middle East, North America, Britain, and ancient Greece — and what he found was that in all these cultures there was a “pervasive concern among men about their masculinity” and a cultural ideal of manhood. He says there was a “contextual universality” — “In all these places, living up to a highlighted image of manhood is a frequent theme” (5).

And what’s interesting about it is that manhood is something you must live up to. Maleness is given, but because masculinity is an ideal and necessary to manhood. Manhood must be earned. And one of the best ways to understand manhood is to compare masculinity and femininity.

Comparing Masculinity and Femininity

We understand both masculinity and femininity better by understanding how they’re different at the universal level. Again, the particular details of application will be different in different cultures, but there is a universality in masculinity, and the Bible assumes this. Natural theology is our go-to. It’s God’s truth revealed in the ways that God has made the world. … which means, we should not be surprised when studies in anthropology and developmental psychology start confirming stuff we already ‘know.’

Leon Podles, whose work I’ve relied heavily upon, has assembled incredible research, drawing a lot from Gilmore as an anthropologist, but also from developmental psychology. Podles cites findings that confirm males are more aggressive than females, even from infancy.[6] “The reaction of testosterone and adrenaline gives a pleasurable high, encouraging men to seek danger” (39). The “science” now backs this up, but it’s the kind of stuff I see everyday!

This is why I can sit at my desk and look out my window and see my young daughters over there playing with their dolls, problem-solving in their pretend home, and meanwhile, my boys are climbing on the roof to jump on the trampoline. In general, boys are inclined to danger and exploration much more than girls (which makes sense given their calling to lead, provide, and protect at the risk of their own lives).

Podles argues that the main difference at work here between masculinity and femininity is that masculinity is characterized by separation, and femininity by communion. This is important. It’s different from activity and receptivity. Some have said that’s the key difference — that men are more active, women more receptive. But that breaks down quickly, because both active and receptive actions are required for masculinity and femininity, and there are masculine and feminine ways to express them.[7] Podles has convinced me that the more accurate difference is separation/integration.

Femininity is internally-oriented and it seeks to host and unite and relate. Femininity seeks to bring things together in here [womb-like]. But masculinity is externally-oriented, and it has a strong sense of agency. Podles says that masculinity seeks to act on the world to change it rather than simply holding it together. Masculinity does naming, brings clarity, draws lines, moves out, traverses frontiers, even at great risks with a willingness to suffer pain. Podles writes,

To be masculine, a man must be willing to fight and inflict pain, but also to suffer and endure pain. He seeks out dangers and tests of his courage and wears the scars of his adventures proudly. He does this not for his own sake, but for the community’s, to protect it from its enemies, both human and natural. Masculine self-affirmation is, paradoxically, a kind of self-[renunciation]. A man must always be ready to give up his life. (43)

But now, we must understand this: masculinity is dynamic, in that, masculinity is not a state or quality that can be possessed, but it must always be practiced.[8] Podles says that masculinity is best understood as a trajectory. … it’s a journey or a quest. (The only way you arrive at manhood with complete assurance is by sacrificial death.) Otherwise you have to be continually acting like a man. This is why manhood is a pursuit.

Getting to the Pursuit

This has been the biggest “aha” moment for me as I’ve studied this the past few years, initially intriguing when I read Robert Bly’s book, Iron John: A Book About Men.[9] This idea of manhood as a pursuit is very different from womanhood. Womanhood is a natural progression. There are clear physiological changes for girls when they become young women — and monthly reminders of that change. Women carry this change inside them as they develop new sci-fi potentialities (i.e., childbearing).

But when does manhood begin?

I’m gonna tell you when manhood begins, but remember that manhood isn’t accomplished irrevocably by a single act (apart from a sacrificial death). Manhood is a pursuit where you are continually needing to prove you are man. It’s an ideology. But here’s where it starts — and this comes from Gilmore’s research, looking at several different cultures all around the world — one thing they all had in common was this: boys become men when the other men around them tell them they are.

And one of the reasons we have a man-crisis in America, and in our churches, is because too many adult males have never had an older man look them in the eyes and say “You are a man.” Men are lost because they don’t even know when they started.

So there’s powerful opportunity for us here, brothers. If I’m honest, the reason I know I’m a man is because I have trusted men in my life who tell me I am, starting with my own dad, but requiring other men also. Does that mean I’m all done? Manhood now achieved? Not at all. Remember it’s a pursuit!

This means: if, God forbid, I were lose my mind tomorrow and leave my wife and eight children and run off to Mexico, if I were do that, I would fail in manhood. I would not be a man if I do that, and none of you would consider me to be a man. But, see, one of the reasons I don’t do that is because other men in my life are saying to me: You are a man, act like one.

That’s what Life Group is supposed to be. That’s what Christian men do for each other. Fraternal affirmation, which is followed by accountability. There must be both.

Because: being a Christian the fulfillment of your manhood, and in no way contradicts it.

II. The Presence of Pursuit in the Christian Life

Something I appreciate about Leon Podles is this book is that he’s mainly doing historical analysis, but he’s also writing as a Christian, and my favorite chapter is Chapter 5: “God and Man in Early Christianity: Sons in the Son.”

He says, right away, at the start of that chapter,

Human masculinity, whose purpose is the protection and provision of the community, finds its fulfillment in the one who is Lord because he is sacrifice and savior. (75)

This is what leads Podles to say that Christianity has a “masculine feel.” Now, I need to be clear here. This does not mean that Christianity is exclusively masculine, but it is thoroughly masculine — and this is something the early church seemed to understand better than we do today. The difference here has to do with the individual and corporate perspectives on Christian identity.

The Bride of Sons

And the corporate level, what is the church called? … the bride of Chris — which is feminine.

In Scripture the church is a feminine personification — the daughter of Zion, the bride of Christ which he cherishes. The church is the inter-relation of individuals in Christ. It’s a communion — and therefore, it makes sense that it’s feminine (think integration).

But on the individual level, to become a Christian is to become a son. Podles writes,

The Son, by pouring forth the Holy Spirit, creates other sons. He conforms both men and women to his own image as Son, by that making them all God’s sons (not daughters). God has no only-begotten daughter; he therefore has no daughters begotten of the Spirit, only sons. There is only one pattern for both men and women to be conformed to, that of the Son. … Christians are the children of God, growing into the image of the Son, that they may also become sons of the Father. (87)

The whole church together is personified as a bride; every Christian as an individual becomes a son. It’s hard to overstate this, men. We need to be very clear: Jesus is not your boyfriend; he’s your brother. You do not relate to him effeminately; but with the kind of fraternal love and loyalty we see between a soldier and his captain. And the early church knew the difference here.

At the individual level, in the early church, to be a Christian meant you are taking an incredible risk. It was dangerous. Persecution and martyrdom were real possibilities. Podles writes,

To be a disciple of Christ is to imitate Christ, and the key event in the life of Christ was his death and resurrection. The Christian who is most fully conformed to that death and resurrection is the best imitator of Christ: the martyr therefore most clearly fulfills the Christian call. …

The martyr is the new athlete, the new soldier. His passion is not passive, but active, a battle. The Church felt, therefore, that martyrdom was, properly speaking, a masculine activity. … All Christians, including women, are called to be athletes of Christ, soldiers against Satan, and to act in a masculine fashion in the spiritual realm. (89–90)

The Quest-Orientation

Another way to put this is to say that, in the early church, they understood the quest-orientation of being a Christian. To become a Christian is to embark on a journey.

Now that idea is embedded in the idea of discipleship, and it starts with conversation. The whole idea of conversion is a kind of initiation. You forsake one way of life, dying to that way, to be born again to a new way of life. You begin a quest. And that quest is most was most obvious in the face of persecution.

The Western use of the term sacramentum to describe the liturgical actions of the Church carries military overtones. The [origin of the word] sacramentum was the oath sworn by the soldier inducted into the army, and it transformed his life. He put aside all civilian concerns and henceforth devoted his life entirely to military affairs. Civilians were dismissed in soldier’s slang as pagani, hicks, and Christians took over the term to describe those who had not enlisted in the army of Christ. Such use of military terminology emphasized the agonic nature of the Christian life, the struggle with Satan and all the forces of evil. The soldier has always been a potent image of the self-sacrificing savior. (Podles, 88)

This image works best when the enemy is a clear, external, physical force.

But, historically, when the threat of martyrdom quieted down for the church, there was a loss of the quest-orientation. (This is one reason the monastic movement emerged.) There was still an enemy. Satan was still seeking to destroy the church, but post-persecution conflict was not expressed by physical, external forces and authorities, but through spiritual forces and personal, inward conflicts. Monks made this pivot, but Christian men at large did not, and the church became less relevant for them. It’s documented that men began to leave the church by the late Middle Ages. Externally-oriented men didn’t see their place in the church; internally-oriented women, with their domestic concerns, carried more influence. It’s worth noting here that although the office of clergy has been exclusively male until the 20th century, clergy in Western literature are largely portrayed negatively, either effeminately or repressively. While there are exceptions, clergy, at the least, are usually “portrayed as simpletons with little depth or complexity.”[10] In general, Western Christianity has been heavily shaped by women for several hundred years, and it appeals less to men than it did in the early church.[11]

As a way forward, I believe it is vital for us to recover the quest-orientation of the Christian life. That the Christian life is a journey against external and internal forces. That is the whole genius of Pilgrim’s Progress (1678). Bunyan shows us that the Christian life is a quest, and half of the battles are internal, and we must deal with them along the way (Slough of Despond and Doubting Castle), and other battles are external (Apollyon and Vanity Fair). Again, this is what discipleship is about. It’s the third vow we take in our baptism (an initiation ceremony).

Do you intend now, with God’s help, to obey the teachings of Jesus and to follow him as your the Lord, Savior, and supreme treasure of your life?

When we take that vow we are enlisting ourselves in a quest. And we get this from the New Testament. The athletic and soldier metaphors are meant to shape the way we think about what we’re doing — we’re running and fighting and farming and building. We just saw a few weeks ago, the wonder of Philippians 3:13,

But one thing I do: forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus.

Here’s what I want you to nail down: The Christian life is a quest.

And because manhood is also a quest, the Christian life is the fulfillment of your true manhood. You cannot become a true man unless you become a true Christian — a true Christian is one who is converted, born again, enlisted in the pursuit of conformity to Christ, through pain.

I think this is the most important aspect of the Christian life that we need to recover. We’re not justified by faith to sit on our hands and be comfortable until we die. We are justified to run —

Run, John, run, the law commands

But gives us neither feet nor hands,

Far better news the gospel brings:

It bids us fly and gives us wings

Brothers, now more than ever, for our families, our church, and these cities, it’s time to fly.

We should seek to become as Christlike as is possible for a forgiven sinner this side of heaven, and we should move out into these cities and this world with agency. We want to act upon this world to make it different from how we found it, for the good of humanity and the glory of God.

We do this because we are Christian men.

* * *

Endnotes

[1] Kevin Vanhoozer calls these the chromosomal marker, the cultural marker, and the consciousness marker. See fn. 3, p. 27 in Designed for Joy: How the Gospel Impacts Men and Women, Identity and Practice (Wheaton: Crossway, 2015).

[2] See Jon Tyson, The Intentional Father: A Practical Guide to Raise Sons of Courage and Character (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2021). See review by Ian Harbor.

[3] See Chapter 1, “Being a Man and Acting Like One” in Designed for Joy.

[4] See Kevin DeYoung, “Play the Man,” Journal for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood 16, no. 2 (2011): 13.

[5] David Gilmore, Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity (New Haven: Yale, 1990).

[6] Leon Podles, The Church Impotent: The Feminization of Christianity (Dallas: Spence, 1999).

[7] “The masculine is a pattern of initial union, separation, and reunion, while the feminine is a maintenance of unity. This pattern is found on the biological level, and even more on the psychological, anthropological, and cultural levels. Femininity is not merely receptivity or passivity, as some have thought. Activity and receptivity are both proper to the masculine and the feminine in distinctive ways. The maintenance of unity typical of the feminine may not be as obviously a state of activity as the pattern of separation and reunification typical of the masculine, but the integration of personality, social unity, and love require effort.” (Podles, 45)

[8] The one exception here might be war. The battlefield is one place where manhood can be “sealed,” as it were.

[9] Robert Bly, Iron John: A Book About Men (New York: Hachette Books, 1990, 2020). I recommend Bly’s book with caution. It’s weird. It stems from the mythopoetic men’s movement of the late 1980s and early 1990s. This movement has some Evangelical spin-offs, as I understand it, such as Promise Keepers, and the popular book by John Eldredge, Wild at Heart: Discovering the Secret of a Man’s Soul (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2001).

I read Wild at Heart as an undiscerning college freshman and I loved it. Within a couple of years, after reviews were published that detailed the theological errors in the book, I backed off. There are indeed serious theological gaffes in the book, such as Arminianism and Open Theism, and we should reject those unreservedly. At the same time, though, there are still insights about masculinity that are worth remembering. Eldredge is like Bly, just a more Christian version, but caution is still advised.

Interestingly, Asher Packman, an Australian thought-leader, is a contemporary voice in the way of Robert Bly. He has lectured on the mythopoetic men’s movement, and on Bly in particular, available at “‘Iron John’ and the Mythopoetic Men’s Movement” (2021). Packman comments that Bly needs to be updated “for the times,” by which he means that it should be made more inclusive, not only applying to men, but to “all genders.” This line of woke thinking is actually what will ruin Bly’s insights about masculinity. While I consider Packman’s summary of Iron John to be helpful, I disagree with some of his analysis.

[10] See Leland Ryken, Phil Ryken, and Todd Wilson, Pastors in the Classics: Timeless Lessons on Life and Ministry from World Literature (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2012).

[11] In Western Christianity, and in particular America, there are more women who are Christians than there are men who are Christians — true for mainline churches as well as Evangelical and Fundamentalist churches (not the case for Eastern Orthodoxy). This has been the case for well over a century (cf. the 1936 census, 1952 adult Sunday School study (53/47), which grew 60/40 women in 1986;). The data is overwhelming.

“Not only do women join church more than men do, they are more active and loyal. Of Americans in the mid-1990s, George Barna writes that “women are twice as likely to attend a church service during any given week. Women are also 50 percent more likely than men to say that are ‘religious’ and to state that they are ‘absolutely committed’ to the Christian faith” (see Podles, 11).

Currently (6-21-2024), at our own church, of our 348 members, we have 169 men; 179 women.